Hello again. I want this to be a user friendly site so here is your chance to get to know me better.

I was born on the 10th of May 1938 and my parents lived in the small town of Brandon in Suffolk, England. Sixteen months later Hitler invaded Poland and the Second World War began. My only direct memory of that was when the air raid sirens sounded and we infants in the local county primary school had to scuttle from our baby size desks and crouch down close to the schoolroom wall.

My father helped to man an anti aircraft battery in Norwich and after the war worked at a local sawmill. My mother cleaned the local cinema and then cleaned shop and home for a High Street shop owner. I had a happy childhood, swimming and fishing in the River Ouse and roaming wild through the fields and woods when I was not in school. I collected birds eggs (All the boys did it in those days), and knew every nest and climbed every tree for miles around. We lived by the seasons, snowballs in winter, marbles in the spring, and lazy hot summers by the river, swimming and fishing. Autumn was for playing conkers, scrumping apples and harvesting blackberries, hazelnuts and wild marabella plums. It was a natural cycle which today’s kids seem to have lost.

At school I was good at reading, with mixed reports for writing. I cut my reading teeth on Rupert Bear, then all the Just William books. I avidly read boy’s comics like the old Beano, the Rover, the Champion and the Eagle. I discovered Tarzan and the Mars books of Edgar Rice Burroughs and read and re-read and re-read the lot. Much later I went to University and read philosophy.

In one school year it was possible to win two stars for every weekly writing composition, one for content and one for neatness of handwriting. I always won one star, but I had to read my composition aloud. My hand flew too fast, trying to keep up with the brain-flow, the pens always leaked and my hand-writing was an illegible mess of blots and smudges. One teacher called me “Smith-plus-ink-equals-a-mess,” and was amazed when he later heard that I had written and published a book. Another teacher in my last school year tried to tidy my handwriting by making me re-write the same composition every week. I soon got bored with that, gave up trying the impossible and simply scribbled the thing through as quickly as possible so that I could get back to reading under my desk. I finally got caught reading “The Rustlers of Rattlesnake Gulch” and was never allowed to forget it. Every time I was late for class the teacher would solicitously enquire whether I had been delayed by the Rustlers in Rattlesnake Gulch?

At an early age I ran errands for neighbours and aunts for three pence a time, and then found a before and after school errand boy job with the chemist shop in the High Street. I left school at fourteen and went to work in one of the saw-mills. Opportunities were limited in Brandon, if you were a boy it was the saw-mills, the forestry commission or one of the two rabbit-skin factories. If you were a girl it was only the rabbits. Your dad or your uncle simply had a word with the foreman to, “Get you in.” In those days every school leaver would be employed.

Standing at the back of a saw bench, choking on saw-dust and deafened by the scream of the band saws and circular saw blades didn’t seem like much of a future. I wanted to see the world, and, more important, let the world see me, so at seventeen I joined the Merchant Navy. I washed dishes all the way to Argentina on the Highland Brigade. The pantry had this useful little circular wall safe where we would, “save for later,” all those awkward dishes that would come in after we had cleaned down. Half way through the voyage the Head Waiter was wondering where all his plates had disappeared to.

I did a second voyage on the Highland Brigade, the same ports, Lisbon, Rio, Santos and Buenos Aires, but this time I was a saloon boy with unlimited access to all the side table food delicacies and the sea air provided a healthy appetite. After that I changed ships and did one trip to New Zealand via Panama on the Rangitiki, and another on the Dunnotter Castle around the coast of Africa.

I worked in the ship’s steam laundry on the Dunnotter Castle. In the tropics we started at two o’clock in the morning to get the job done before the worst heat of the day, but even so I could wipe the dripping sweat off my bare chest and watch the bubbles immediately seep through my skin. We were fed an extra diet of salt tablets to make up the deficiency. I only took the job because the ship was due back in England for Christmas.

As things happened, Egypt’s President Nasser chose that year to close the Suez Canal. We missed the last convoy through the canal by twenty minutes, which was fortunate because the tail end ships in that convoy were sunk by the Egyptians to block the Canal. The bulk of the convoy were trapped there for almost two years. The Dunnotter Castle was ordered out of the Mediterranean so we circumnavigated Africa counter clockwise all the way up the east coast to Mombassa, and then had to return the same way. I spent my second Christmas at sea and didn’t get home until February.

Because the ship was so far behind schedule port calls were quick and hurried and there was no time for shore leave. I got disillusioned and quit the Merchant Navy. I tried to join the army for three years, hoping for postings to Hong Kong or Singapore, but because of an old bone disease of the hip that had kept me on crutches for a year when I was eleven my services were declined. I tried to rejoin the Merchant Navy but three liners had just been decommissioned putting a thousand stewards out of work. I actually went on board and got a job on the P&O flagship Canberra, again heading for the magical orient, but the all-powerful seaman’s union wouldn’t let me take it up.

Then began a period of short term shore jobs; labouring on building sites, factory work, bar work, holiday camps, anything that came along, broken up by passionate marathons of full time writing. I had started keeping a diary in the Merchant Navy, full mainly of flowery descriptions of the ports and places I had seen. Without this to inspire me I delved into my imagination and began writing short stories. By now I had purchased my first typewriter and the blots and smudges of boyhood were behind me. I wrote over 200 short stories and after taking a short story writing correspondence course I eventually sold about two dozen to markets like Reveille, Weekend, Titbits, the London Evening News and the old John Creasy and London Mystery magazines.

My first novel started out as a short story, became a long story, then a short novel, and finally a full length novel. It was about the aftermath of a nuclear war, a very topical subject at the time, but as a first effort it didn’t sell. There were three more non-sellers before I wrote The Faceless Fugitive, which was published by Robert Hale. It also sold to Odham’s Man’s Book Club and was serialized in a French TV magazine. My writing career was launched.

My second novel was Nothing to Lose, the first in a long series featuring Simon Larren, the killing arm of British Counter Espionage. I had three books written and published before the first James Bond film was made and was poised to catch the rising tide of spy mania. Suddenly every bookshop window in Europe was filled with books with the word ESPIONAGE printed large on every cover, and my books were there with the rest.

I was then writing as ROBERT CHARLES, which were my Christian names. In between the bread and butter jobs I was soon writing four thrillers a year for Robert Hale until eventually they asked me to add another pen-name. My mother’s maiden name was Leader and so I chose CHARLES LEADER and alternated my books between those two pen names for the next twenty years. Hale also acted as my agent and soon began selling many of the translation rights to my books in France, Italy, Germany and Scandinavia, and finally in the USA. When the money came in I went travelling, searching the globe for new ideas and new exotic backgrounds.

I owned a series of three motor cycles. The first one took me all around the British Isles. The second one took me all around Europe. The third one took me all around Greece. My first car was a little blue Austin A30 which took me down through Spain and all around Morocco. I rode on the Orient Express to Istanbul, flew to Cairo and carried on up the Nile to the Valley of the Kings. Between each trip I was writing or working at another fill-gap job.

The writing process in those days ideally involved a visit to the planned location, keeping an extensive diary and collecting up all the city maps and tourist literature available. Then I would read up all the travel books I could find on that particular country. That soaked up the background and stimulated plot ideas. I also kept extensive press cutting files to stimulate more ideas and make sure all my political and military information was right up to date. I had files on every country in the world and those early trips gave me titles like Stamboul Intrigue, Nightmare on the Nile, and Murder in Marrakech.

Today of course the internet makes background research so much easier, but the old way was much more exciting and much more fun.

My first overland trip to India was with a group called The Overlanders. There were about thirty of us in two clapped out old buses. The aim was to sell the buses in Kathmandu but the blue bus didn’t make it past Persia and the red bus our leader sold in Kabul. I hitched with one of the girls to Kathmandu and then continued alone through South East Asia to Hong Kong and Japan. At last I had reached the exotic orient.

I did a second overland bus trip with a group called the Indiaman, filling in the gaps and making a much more intensive tour around India, Thailand and Cambodia. Both India trips ended with a return via Siberia and Moscow. My final overland adventure was the trans-Africa trip with Siafu, fourteen of us in two Land Rovers driving from Tunis to Capetown.

After the Africa trip I joined the Suffolk Fire Brigade as a retained fireman at Brandon. The camaraderie of fire-fighting, the thrill of riding that big red engine with the blue light flashing, and the satisfaction of dealing with fires, road accidents and other emergency scenarios proved the perfect complement to the lonely grind of a writer. It was also the perfect supplement to an erratic and uncertain income, much better than the previous round of boring temporary jobs.

During one long hot summer, in between fighting fires and writing books, I built a bathroom and kitchen extension on to my mother’s cottage. Most of the time I worked stripped to the waist and caught the eye of a charming young widow. My writing career had reached its peak. My new Counter-terror series had sold to Pinnacle in the USA and I had sold two film options. Elizabeth had appeared and suddenly I was rich enough to get married. Elizabeth had been left with three young children so now I had become a family man with a whole new range of responsibilities.

We had our honeymoon in Paris and then took Christopher and Andrew and Michelle on a family bonding holiday at one of Billy Butlin’s Holiday camps. My editor at Pinnacle commissioned two books on the outlines and persuaded me to move to a new agent. My agent worked wonders. Suddenly I had branched out into horror and science fiction and had five books commissioned on outlines. In addition to the foreign translation sales I had five publishers in the UK and USA. Writing in the bedroom wasn’t working any more so I built a large brick garage and converted the back end into my writing office. It became known as “Dad’s Den.”

As abruptly as my romantic life had magically changed for the better my writing life crashed horribly into reverse. The world plunged into an economic recession. Publishing was particularly badly hit and everything was snatched away. The film options never materialized into films. Paramount, the new UK publishing venture launched by Pinnacle with myself as lead author was killed dead by Pinnacle’s accountants. My Pinnacle editor had moved to Harlequin to head up a new imprint but the two books he had commissioned for me there were cancelled with the imprint itself. Suddenly I was getting kill fees to write off everything in my writing pipeline. By the time the dust had settled most of my editors had disappeared, their companies also vanished or been swallowed up by the new conglomerates that were the new face of publishing. Even Robert Hale who had published over forty of my crime, spy and political thrillers, had now pulled out of the thriller market altogether.

Foolishly I tried to fight back. My contract with one of the mainstream paperback publishers didn’t leave them a get out clause after the book had been completed and accepted. I sought legal advice and reluctantly they did publish a handful of token copies. It was a hollow victory and here is an important writing tip. Unless you are a celebrity, or so well established that you sell millions of copies anyway, never challenge a publisher. My agent dropped me like the proverbial hot potato and I have never again sold anything to one of the mainstream publishing houses.

We had moved to a new home in Bury St Edmunds and I now had a mortgage to pay and a wife and children to support. I found another dead-end factory job but what I really needed was a new career. I went to the West Suffolk College to enquire about night school and getting some O-level qualifications. As soon as the principal learned that I had published more than forty books he pointed out that I could by-pass both O and A levels, and apply to go direct to University. In those days I could get a mandatory government grant to pay my tuition fees, pay my mortgage and keep myself and my family. I grabbed the opportunity and went for it.

I spent the next three years at the University of East Anglia, studying philosophy as my major subject with a split minor in Social Anthropology and Politics. I emerged with an upper second class degree. In effect I went to University unemployed and came out unemployable. Nobody wanted a forty-eight year old graduate. The big companies were all looking for the fresh-faced, still malleable youngsters in their twenties.

I had hoped to get into advertising. I had done some freelance copywriting for the local advertising agencies in Bury St Edmunds, and believed that with this, my previous writing experience and a degree I could get into one of the big London agencies. Too late I learned that most advertising executives retired at fifty, even at thirty if they had not reached senior copywriter or artistic director they usually moved sideways into publicity. At forty eight I had no hope of getting started.

I spent a year applying for jobs and then realized that I had to go self-employed again. Building my mother’s kitchen and bathroom extension, and then building the garage on to our new home to act as my writing room, meant that I had self-learned a whole new range of practical skills. I became Rainbow Painting and Decorating, Home Repairs and Maintenance. I had transferred from Brandon fire station to the fire station at Bury St Edmunds and throughout my three years at University I had continued to answer calls as a volunteer fireman during the vacations. I was again on the retained crew so I continued to fight fires in addition to my new work routines of painting, wall-papering, tiling, bricklaying and carpentry. Elizabeth had taken her O levels and begun a career in nursing. The children grew up. Grand-children came along. Life was good.

I collected my twenty years long service and good conduct medal when I retired from the Fire Service at fifty-five. At sixty-four a heart attack put an end to Rainbow Painting and Decorating. However, by then my writing career had flickered back into life. I had discovered Ulverscroft, the market for large print reprints and they had re-published all of my old Robert Hale books in their Lynford Mystery series. With some of the money I had bought a second hand Pentax and a correspondence course in freelance photography. I was soon motoring all over East Anglia and selling photo-features to all the county magazines.

I was interested in heritage, history and places, so initially I was looking for castles, abbeys and stately halls. Then I began to follow the courses of all the rivers, from their sources to the sea. After a while I realized that with each county I was building up enough material for a book. The first two county guide books, In Search of Secret Suffolk and In Search of Secret Norfolk were published by Thorogood who at that time owned Acorn Magazines. When Thorogood sold Acorn Magazines and returned to their core business publishing interests, Exploring Historical Essex was taken up by History Press. For all this new work I had juggled my old writing names and given myself a re-launch. Robert Charles and Charles Leader were dead. As a writer I am now Robert Leader.

As Robert Leader I also wrote and sold my heroic fantasy trilogy The Fifth Planet to Samhain, one of the new e-book publishers.

Now I am seventy four, the world is in another economic recession and my writing is in the doldrums again. History Press are delaying publication of my new book on Cambridgeshire. Ulverscoft who have been publishing my new crime books since we ran out of Hale titles to reprint have now said they can no longer afford an editor, so Serpents in Eden remains unpublished.

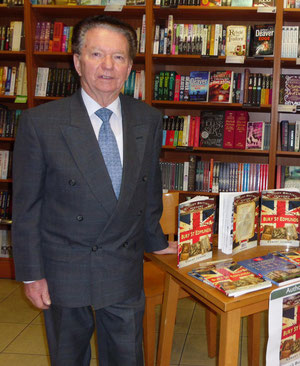

Obviously no publisher is going to give me a new start. I’m not a celebrity and I no longer have youth on my side. With the county guide books I had to write the books, take the photographs, and then sell the books through book signings and talks to clubs and women’s institutes. All of this for only 0.75 % of the publisher’s returns, which worked out at about 30 pence per copy. In this new age of e-books and Kindle readers maybe I can sell my own books on the internet for more than 30 pence each. I still cherish the ambition to sell Extinction’s Edge so what have I got to lose?

Please read the free books. You have nothing to lose either.

If it becomes worthwhile I have a backlist of over sixty unpublished or out of print books which I can put up as a free or a low cost read. It’s got to be worth a try. Plus, of course, it will enable me to keep writing.

I’d love some feedback on all of this. If as a writer or a reader you’ve found the site helpful or interesting please let me know. My email address is robertcharlesrleader@talktalk.net

ROBERT LEADER

ROBERT LEADER